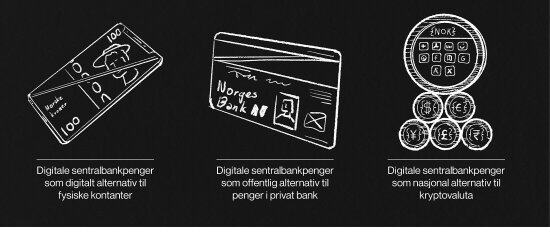

Central banks all over the world are currently exploring central bank digital currencies (known as CBDC). In brief, this is electronic money issued directly by a central bank. Both the Bank of Norway and a number of central banks in other countries are considering how we can use such money in the future.

Glenn Sæstad thinks CBDC is a unique opportunity to steer our society in a more sustainable direction. In his Diploma dissertation at the Oslo School of Design and Architecture he uses design methodology to investigate how central and local government can use this kind of money in order to encourage businesses and private individuals to make more climate-friendly choices.

24 experts were interviewed

For his dissertation he had a regular dialogue with the Bank of Norway’s own working group on CBDC. Sæstad interviewed 24 experts in the fields of economics, fintech and public sector innovation. In addition he gathered knowledge and insights from specialist literature on economics and finance.

He then constructed a future scenario based on the possibility that climate change can constitute a direct threat to the financial stability in Norway. Sæstad argues that in such a case, sustainability would come under the mandate of the central bank, at the same time as the public sector would push for more effective transition tools. That would leave the path open for a proactive use of CBDC.

Digital central bank money as a digital alternative to physical money. Digital central bank money as a public alternative to money in private banks. Digital central bank money as a national alternative to cryptocurrency.

Carbon rations and local currency

Carbon rations is one of the financial concepts investigated by Sæstad in his dissertation. While current carbon quotas can be bought and sold and thus favour those with the greatest wealth, carbon rations would affect everyone equally. Having a lot of ordinary money in your account would not make any difference: if you have already spent your ‘carbon cash’ there will be no champagne in Chamonix this Easter.

Another example is to allow localised currency in order to stimulate people to spend more money in their own local communities. In Sæstad’s imagined scenario, the municipality of Egersund established the currency ‘Okka Peng’, dialect for ‘our money’, which can be used for buying goods and services locally. Exchanging normal kroner for ‘Okka Peng’ would give an exchange bonus of a couple of percent so that you would get more for your money by using the localised currency.

But if you change ‘Okka Peng’ into normal kroner you would pay a higher exchange fee than the bonus the other way. In this way, local solutions from locally owned businesses become more profitable for both consumers and companies, while buying things from far away becomes less attractive.

Great consequences for society

The point of the dissertation is not to propose the examples as ready-made solutions, but rather to point to an under-researched direction for CBDC and challenge the Bank of Norway’s thinking about innovation. Sæstad thinks that tethering CBDC to the sustainable goals will create great value beyond the Bank of Norway.

The designer argues that for the Bank of Norway, CBDC as a platform for state innovation would be a way of living up to society’s expectations that the central bank, too, should contribute to sustainable growth, without compromising its independence.

In return, other parts of public administration will have access to a digital infrastructure for spending public money in new ways to reach the SDGs. This will also create value for the citizens, who will encounter a more innovative public sector that safeguards their needs more effectively. A more comprehensive set of tools to help reach the SDGs more quickly will also reduce international factors that affect life in Norway, such as natural disasters, conflict and flows of refugees.

In order to test the project’s relevance, Sæstad has presented his work to a range of groups, both conventional and more radical voices within the field of economics. The dissertation has received much attention and has helped to demonstrate the relevance of the design field for economics.

Project: DSP for SDG

By: Glenn Sæstad, Master in design, The Oslo School of Design and Architecture

Design disciplines: Business design, Design research, Systemic design

Recipient of the DOGA Award

This project has received the DOGA Award for Design and Architecture for its outstanding qualities and for showing how strategic use of design and architecture create important social, environmental and economic value.

These are three reasons why this is an exemplary project:

- Challenges deadlocked thinking

We are faced with a number of challenges which require us to organise our society in new ways. The method and communication ability demonstrated in Sæstad’s project make it possible to challenge deadlocked thinking and prepare the ground for radical change.

- Illustrates the power of future scenarios

The dissertation illustrates how to use future scenarios and speculative design to stimulate discussion and new perspectives. The point of CBDC for the SDGs is not to propose these examples as ready-made solutions, but to demonstrate an under-researched direction and challenge the Bank of Norway’s thinking about innovation.

- Tools to fulfil the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals

The project responds to the UN climate panel’s appeal for a fast-track cross-sector climate effort using all possible means in order for the planet to exceed the goal of 1.5 degrees by as little as possible. It does this by exploring how the financial system which strongly influences everything in society can support the work on achieving the SDGs.